In Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters To A Young Poet (1984), he addresses the idea of isolation, saying that “What is necessary, after all, is only this: solitude, vast inner solitude. To walk inside yourself and meet no one for hours – that is what you must be able to attain” (54). He goes on to describe the feeling one has as a child watching adults walk around involved in things that seem important, but which only seem that way because as a child you don’t understand them. Rilke tells the reader that it’s important to hold onto that “not-understanding”, in order to separate oneself from the rest of society, maintaining one’s own solitude. It’s in an isolated setting, most likely a natural one, surrounded by vastness of trees and rivers or oceans, where creativity is most likely to be found and nurtured. For this to function academically, each student would have a respective space to feel alone in. When in this environment, total creative freedom would be given – students would work on projects based solely on their own yearnings.

Because the idea here is to draw blueprints for an ideal academic setting in which creativity could be stimulated, goals for the students to attain are fundamental in the process. These goals though, would be decided upon uniquely by each student, depending on their ambitions and mediums. Students work on their projects in isolation in order to reach their respective goals. In William Stafford’s A Way of Writing (1970), he illustrates the method in which he writes to be very purposeful, devoting a certain time of the day to his work: “I get pen and paper, take a glance out the window (often it is dark out there), and wait… Something always occurs, of course, to any of us” (615). This guarantee could not be made though, if one had no motivation to create. It is for this purpose that goals must be made; realistic, specific, and attainable ones. However, the goals themselves should be able to change completely, as the mind of a Creative Being is not always one to stay on task. If a student found their path taking a new direction, they would simply have to change their endeavors to suit it.

Every so often, as much as once each day or as little as twice each week, students would wander from their isolated areas of artistic indulgence, and meet all together with their teacher. This is where the teacher has the opportunity to share his or her experience and knowledge with the students, and inspire the class through lecture, conversation, and readings. It is important to remember though, that the idea of these meetings is not for the teacher to teach the students how to be creative, but rather to educate them in the history and beauty of creativity as a subject. Koans, as they’re described by Edward Stephens and Thomas Burke in “Zen Theory and the Creative Course” (1974), are an excellent model for the sort of teaching and learning that should occur in these meetings: “Since the atmosphere of monastery life alone cannot produce Enlightenment, just as the classroom alone cannot bring forth creativity, Zen training also relies on the interaction between the Master and his students. This takes the form of questions (called Koans) to which the student must respond. His response, coming from his soul, is a reflection of his nature, and therefore, is not to be judged as right or wrong by the Zen Master” (40). The difference is that Koans take days for students to answer, whereas the lessons and discussions had in these meetings must be kept within that meeting, and must arrive at some sort of conclusion. Students must not have any work or problems to distract them from their own projects once they’ve returned to their camps – to their easels, desks, floors, silence.

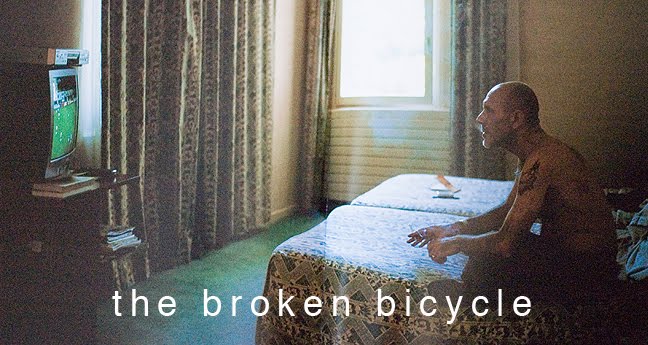

Now a step back must be taken from all of these words. Look at the blueprints from a distance. This is what they look like: There is a camp, probably somewhere deep within the woods. There are cabins with vastness between them, arranged in a circle. There is a student in each of the cabins. There, the student works alone on whatever art it is they feel the need to work on – they fill their days with productivity of art and love, because what else but those two things is able to fill nothingness? The projects they work on are based on goals made and remade throughout the course, depending on where their musings take them. In the center of the circle, there is a meetinghouse. This may also be the residence of the teacher; the mentor. This is where once every so often the group of students will assemble and their minds will all work together to answer questions or to simply soak in or tune out what the teacher wants to fill them with – they are encouraged to think critically. By keeping these lessons in the confines of the meetinghouse, students take what they want back with them to their camps, and remain independent. In “A Self-Defining Game for One Player” (2002) Harold Cohen says, “I think of autonomy now in terms of that weakly defined but strongly felt future state that manifests itself in the criteria that direct creative behavior” (64). This autonomy is something that can be tapped into only once a thinker, an artist, a Creative Being of any sort, is not creating for anybody but his or her own satisfaction and release. If that autonomy can be found, it is in some vast solitude. “For,” as Rilke puts it, “what would a solitude be that was not vast; there is only one solitude and it is vast, heavy, difficult to bear…” (54). And with art in mind, these are the greatest conditions one could ask for.

1 comment:

I like the sound of your voice, those songs are nice, Joe. Real nice.

Post a Comment